Sustainable Living at Ballinderry Park: A Blueprint for Heritage-Led Regeneration

Rowan Stainsby

In an age where sustainability has become a corporate buzzword stripped of its deeper meaning, Ballinderry Park stands as a living counterargument. This isn’t a story about solar panels and recycling bins, though those elements exist. This is about something more fundamental: the reclamation of an ancient relationship between people, land, and community that industrial modernity nearly erased. It’s about what happens when conservation meets collaboration, when heritage becomes not a museum piece but a working model for regeneration.

Ballinderry House nestled among ancient trees

Ballinderry House stands as a testament to architectural heritage preserved through active stewardship rather than static conservation

The Philosophy of Place: Rethinking Sustainability Through Heritage

When we speak of sustainable living, we typically invoke images of modern eco-villages, net-zero buildings, and cutting-edge green technology. Ballinderry Park challenges this forward-only narrative by looking backward—not in nostalgia, but in recognition of wisdom nearly lost. For seven centuries, this estate has been a working landscape, and that continuity itself represents a form of sustainability that transcends any single generation’s innovation.

The concept of “heritage-led sustainability” emerging at Ballinderry Park is deceptively simple: the practices that allowed this land to thrive for 700 years contain lessons urgently needed in our current moment. This isn’t romantic pastoralism. It’s the recognition that modern industrial agriculture, food systems, and community structures have created ecological and social debts that cannot be repaid with technology alone. The solution requires relearning ways of being that were systematically dismantled during the twentieth century’s rush toward efficiency and consolidation.

The Estate as Ecosystem

At Ballinderry Park, sustainability begins with understanding the property not as a collection of assets but as an integrated ecosystem with human activity as one element among many. The ancient woodlands, meadows, waterways, and agricultural lands form a complex web of relationships developed over centuries. Modern sustainable practices don’t replace this system but enhance and protect it, working with rather than against the land’s inherent character.

This approach manifests in seemingly small but profound choices. Habitat corridors are maintained for native wildlife. Historic hedgerows, which would be removed on industrial farms for efficiency, are preserved as crucial ecosystems supporting dozens of species. Ancient tree specimens are protected not just for their aesthetic value but for their role in soil health, carbon sequestration, and biodiversity support. The estate operates on the principle that every element serves multiple functions—ecological, aesthetic, cultural, and economic—and that disrupting one thread affects the entire tapestry.

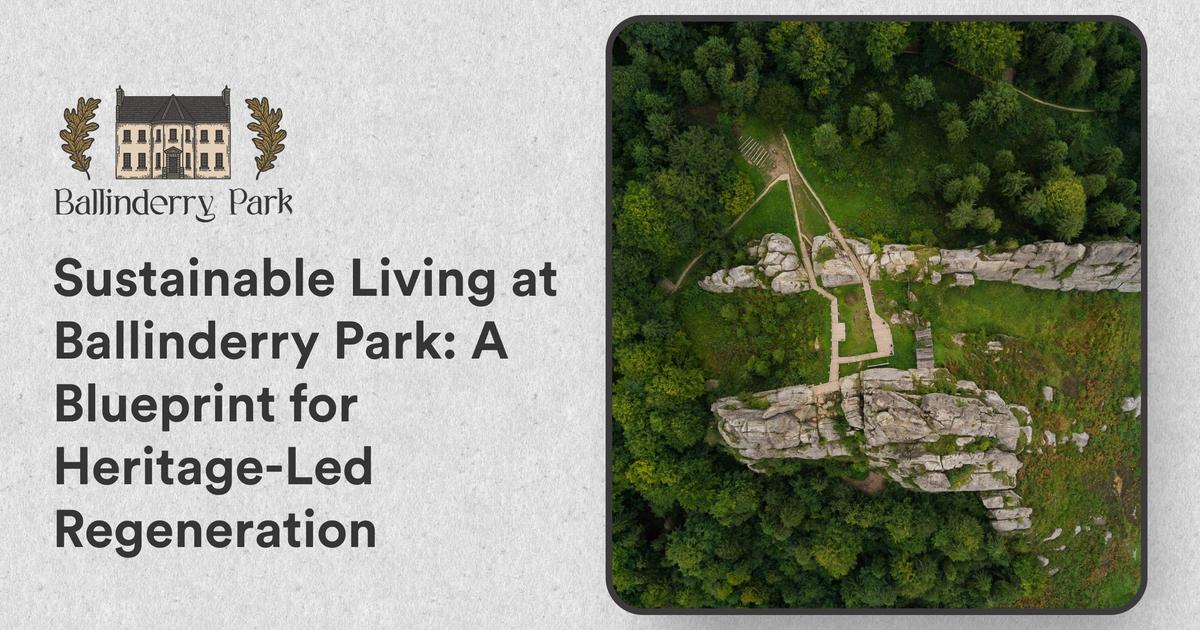

The expansive grounds of Ballinderry Park

The estate’s landscape represents centuries of co-evolution between human stewardship and natural systems

Be Part of the Story

Ballinderry Park’s vision depends on community participation. Discover how you can contribute to heritage-led sustainability in East Galway.

Estate-Sourced Food: Radical Localism in Practice

The phrase “farm to table” has been commercialized to meaninglessness, often describing food that travels hundreds of miles while technically coming from “local” industrial operations. Ballinderry Park’s approach to estate-sourced food represents something categorically different: a closed-loop system where the relationship between land, animal, harvest, and consumer is transparent, immediate, and accountable.

The Venison Economy

The estate’s venison program exemplifies this philosophy in action. Wild deer have been part of this landscape for millennia, and their management represents a delicate balance between conservation and harvesting. Unlike industrial meat production, which breeds animals in confinement for maximum yield, the estate’s deer live entirely wild, browsing on native vegetation, strengthening their health through natural movement, and contributing to woodland ecology through their grazing patterns.

Harvesting is done selectively and respectfully, following traditional estate management principles that maintain healthy population levels while preventing overgrazing that could damage young woodlands. The meat that reaches tables at Ballinderry Park represents not just food but a story of land stewardship. Diners consuming this venison participate in an ancient cycle: the deer feed on the land, the land is managed for their wellbeing, and careful harvesting supports both the ecosystem and the community that depends on it.

This is sustainability beyond carbon footprint calculations. It’s about reconnecting the act of eating with the ecological realities of where food comes from. When you eat estate-sourced venison at Ballinderry Park, you know the animal lived well, died humanely, and its harvest contributed to the health of the very landscape surrounding you. That knowledge transforms consumption into participation.

Estate-sourced culinary presentation

Each dish tells a story of place, from estate-managed game to locally foraged ingredients

The Pheasant Tradition

Pheasant shooting has long been part of Irish estate life, often criticized as an aristocratic indulgence. At Ballinderry Park, this tradition has been reconceptualized as sustainable food production integrated with habitat conservation. The pheasant population is managed to provide both sport and sustenance, but more importantly, the habitat requirements for healthy pheasant populations—hedgerows, field margins, diverse vegetation—benefit countless other species.

This demonstrates a key principle of heritage-led sustainability: traditional practices, when properly understood and implemented, often align with conservation goals. The game management that sustains pheasant populations creates refuge for songbirds, supports insect diversity, and maintains landscape heterogeneity that industrial agriculture destroys. The pheasant on your plate represents not just protein but an entire ecosystem management philosophy.

Moreover, the skill set required for traditional game management—reading landscape, understanding animal behavior, tracking seasonal patterns—represents embodied knowledge that cannot be replicated by agricultural technology. When estates abandon these practices, they lose not just an activity but a sophisticated understanding of land management developed over generations. Ballinderry Park’s commitment to maintaining this tradition preserves crucial ecological knowledge while providing genuinely sustainable food.

The East Galway Network

While estate-sourced game forms the protein foundation of Ballinderry Park’s food philosophy, the commitment to local sourcing extends throughout East Galway. This isn’t merely about reducing food miles, though that matters. It’s about building a resilient regional food system that supports small producers, maintains agricultural diversity, and creates economic opportunity in rural communities.

Vegetables come from market gardens within a twenty-mile radius. Dairy products originate from family farms where animals still graze on grass, not concrete. Bread is baked using Irish-milled flour from heritage grain varieties. Foraged ingredients—wild garlic, mushrooms, berries—come from the estate’s own woodlands, gathered by staff who learn traditional foraging wisdom. This network of relationships represents sustainable economic development as much as environmental practice.

The True Cost of Local Food

Estate-sourced and locally procured food costs more than industrial alternatives, and Ballinderry Park doesn’t apologize for this. The higher cost reflects true values: fair compensation for producers, environmental practices that regenerate rather than deplete, animal welfare standards that respect life, and the maintenance of skilled rural livelihoods. When industrial food appears cheap, it’s because costs have been externalized—degraded soil, polluted water, depleted communities, confined animals. Ballinderry Park’s food system internalizes these costs, demonstrating what honest pricing looks like in a sustainable economy.

Locally sourced ingredients and estate produce

Every ingredient represents a relationship with a producer, forager, or piece of land

Working with Community to Build a Better Future

The phrase “working with community to build a better future” adorns countless corporate social responsibility statements, usually describing token charitable donations or volunteer days that leave power structures unchanged. At Ballinderry Park, community partnership represents something more structurally significant: the recognition that sustainable futures cannot be built by isolated actors, no matter how well-intentioned, but require collaborative networks that share knowledge, resources, and vision.

The Philosophy of Shared Stewardship

Ballinderry Park’s 700-year history includes periods of both enlightened and exploitative estate management. The current vision acknowledges this complex heritage while consciously choosing a different path forward. Rather than positioning the estate as a private preserve that occasionally grants public access, the emerging model treats it as a shared resource held in stewardship for the broader community.

This manifests in practical ways. Educational programs bring local schools to the estate to learn about woodland ecology, heritage conservation, and sustainable food systems. Workshops teach traditional skills—from foraging to woodland management—that connect participants to place-based knowledge. Community events create space for gatherings that strengthen social bonds, recognizing that sustainable communities require strong relationships as much as sound environmental practices.

But the commitment goes deeper than programming. Community partnership means creating channels for genuine input into estate management decisions. Local knowledge about land, history, and practice is valued alongside expert conservation advice. When conflicts arise between different visions of the estate’s future, resolution is sought through dialogue rather than imposed from above. This requires vulnerability and humility rare among institutional landowners.

Economic Development Through Heritage

One of the most persistent tensions in rural sustainability is the conflict between conservation and economic development. Communities struggling with unemployment and population decline understandably view conservation restrictions as threats to livelihoods. Ballinderry Park attempts to resolve this tension by demonstrating that heritage preservation can be economically generative.

The estate creates employment across a range of skilled and unskilled positions: hospitality staff, groundskeepers, conservation workers, kitchen teams, maintenance crews, administrative roles. These aren’t extractive positions that deplete resources for profit elsewhere but regenerative jobs that maintain and enhance the very asset providing employment. The work has dignity because it serves a purpose beyond profit—the preservation of heritage for future generations.

Moreover, by sourcing from local producers, the estate creates secondary economic benefits throughout East Galway. The vegetables served at dinner support market garden operations. The dairy in coffee sustains family dairy farms. The wool in furnishings comes from regional sheep operations. This multiplier effect demonstrates how anchor institutions can catalyze sustainable rural economies when they commit to local sourcing.

Sustainable Community Begins With Connection

Learn about volunteer opportunities, educational programs, and partnership initiatives at Ballinderry Park.

Community gathering space at Ballinderry Park

Creating shared spaces where community connections flourish alongside environmental stewardship

The Shared Space: Where Food and Nature Create Community

Ballinderry Park describes itself as a “shared space where great food and love of nature bring people together.” This simple statement contains a sophisticated vision of what sustainable living actually means at the human scale. Sustainability isn’t about individual consumer choices or technological fixes but about creating conditions where people naturally come together around shared values and practices.

The Power of Convivial Spaces

The philosopher Ivan Illich wrote about “conviviality”—spaces and tools that enhance human autonomy, creativity, and connection rather than reducing people to passive consumers. Ballinderry Park functions as a convivial space in this sense. When visitors gather to share a meal of estate-sourced food, they participate in something fundamentally different from a restaurant transaction. They enter a space of abundance that doesn’t depend on exploitation, beauty that doesn’t require ecological destruction, and pleasure that strengthens rather than weakens community bonds.

The physical environment supports this conviviality. Dining spaces look out onto the landscapes that produced the food on the table, creating visible connection between consumption and source. Gardens and grounds invite exploration, encouraging people to move beyond passive consumption into active engagement with place. The pace is deliberately unhurried, resisting the efficiency imperative that degrades so much modern life. Time spent at Ballinderry Park isn’t time optimized but time inhabited, and that distinction matters profoundly.

Food as Cultural Practice

The emphasis on “great food” at Ballinderry Park isn’t about gastronomic novelty or fashionable cuisine but about food as cultural practice—the centerpiece of human gathering and meaning-making since time immemorial. When food is produced sustainably, prepared skillfully, and consumed communally, the act of eating becomes sacred in the original sense: set apart from ordinary commerce, connected to something larger than individual gratification.

This approach to food stands in stark contrast to industrial food culture, which treats eating as refueling, a necessary interruption in productivity. At Ballinderry Park, meals are central events around which other activities organize. This isn’t inefficient; it’s properly ordered life. When food becomes central again, many sustainability challenges resolve themselves. People who care about meals care about ingredients. People who care about ingredients care about land. People who care about land become stewards. The sequence is ancient and reliable.

A shared space where great food and love of nature bring people together isn’t marketing language. It’s a theory of change—the belief that sustainable futures emerge from embodied experiences of abundance, beauty, and connection rather than guilt, scarcity, and isolation.

Nature as Participant, Not Backdrop

Many rural hospitality operations treat nature as scenic backdrop—beautiful but essentially passive, something to look at while the real action happens indoors. Ballinderry Park’s vision positions nature as active participant in the experience. The woodland walks aren’t amenities but invitations to relationship. The estate’s wildlife aren’t attractions but neighbors. The changing seasons don’t provide decorative variation but structure the rhythm of life, determining what foods appear on menus, what activities become possible, what moods pervade the atmosphere.

This integration of human and natural cycles represents sustainability at its most fundamental. The industrial worldview treats nature as resource to be extracted or problem to be managed. The Ballinderry Park approach treats nature as context within which human flourishing occurs. This shift in relationship—from domination to participation—underlies every sustainable practice on the estate. You cannot simultaneously view nature as participant and treat the land exploitatively. The mindset prevents the practice.

The Grey Room Suite interior at Ballinderry House

Interior spaces honor historic character while providing contemporary comfort, demonstrating sustainability through preservation

Heritage Preservation: The Most Radical Sustainability

In a culture obsessed with novelty, constantly demolishing the past to make room for the next development, preservation itself becomes a radical act. Ballinderry Park’s 700-year continuity represents a form of sustainability that makes most modern “green” developments look frivolous by comparison. What could be more sustainable than maintaining a structure for seven centuries instead of demolishing and rebuilding every few decades?

Embodied Energy and Cultural Memory

The concept of “embodied energy”—the total energy required to produce a building or object—has gained currency in sustainability circles. By this measure, the most sustainable building is always the one that already exists. Ballinderry House represents an enormous quantity of embodied energy: the quarrying and shaping of stone, the harvesting and milling of timber, the manufacture of fixtures and fittings, the skilled labor of craftspeople now long dead. All of that energy remains captured in the structure, serving present needs without requiring new extraction.

But the calculation goes beyond energy. Heritage buildings embody cultural memory, craft knowledge, aesthetic traditions, and regional identity that cannot be quantified or replicated. When such buildings are demolished, something irreplaceable is lost. When they’re preserved, future generations inherit not just shelter but connection to the past, understanding of place, and examples of excellence to inspire future creation.

Adaptive Preservation vs. Static Conservation

Ballinderry Park’s approach to its 700-year heritage demonstrates a crucial distinction between adaptive preservation and static conservation. Static conservation treats historic properties as museum pieces, maintained in pristine condition but essentially dead, cut off from contemporary life. Adaptive preservation maintains historic character while allowing buildings to serve present needs, keeping heritage alive through use rather than embalming it through isolation.

This philosophy manifests in practical decisions throughout the estate. Historic structures are maintained using traditional materials and methods, preserving craft skills that might otherwise disappear. But modern systems—heating, plumbing, electricity—are integrated sensitively to ensure comfort and function. The result is heritage that serves life rather than life serving heritage, a sustainable balance that allows the past to enrich the present without constraining it.

The approach also applies to landscape. Ancient trees are protected and veteran specimens monitored for health issues. But new trees are planted to ensure canopy continuity for future centuries. Historic garden layouts inform but don’t dictate contemporary planting schemes. Traditional agricultural practices are maintained where they serve sustainability goals but modified or abandoned where they don’t. The result is a living landscape that honors its past while adapting to present ecological understanding.

Heritage as Resistance

There’s a subversive element to heritage preservation that’s often overlooked. In a economic system dependent on continuous consumption and planned obsolescence, maintaining something for 700 years represents resistance. It declares that not everything exists to be monetized and discarded, that some values transcend market logic, that continuity itself has worth beyond economic calculation.

Ballinderry Park’s preservation demonstrates that beautiful, functional spaces can be created without succumbing to the tyranny of trends or the wasteful cycle of demolition and reconstruction that characterizes contemporary development. Every person who experiences the estate receives a counter-education to consumer culture’s messages: old isn’t necessarily obsolete, beautiful doesn’t require new, sustainability means maintaining rather than constantly replacing.

Historic conference space at Ballinderry Park

Historic spaces adapted for contemporary use demonstrate sustainability through longevity and adaptive reuse

Experience Heritage-Led Sustainability

Visit Ballinderry Park to see how preservation, community, and environmental stewardship create a model for sustainable living.

Challenges and Contradictions: The Honest Accounting

Any genuine discussion of sustainability must acknowledge contradictions and limitations. Ballinderry Park operates within systems that constrain even its best intentions. An honest accounting of these tensions strengthens rather than undermines the project’s credibility.

The Tourism Paradox

Ballinderry Park depends on visitors for economic viability, yet tourism itself carries environmental costs. Guests arrive by car, consuming fossil fuels. The hospitality operation requires energy, water, and materials. The very act of maintaining a heritage property for public experience involves resource consumption. This paradox has no simple resolution.

The estate’s response is not to deny the paradox but to minimize harm while maximizing regenerative benefit. Encouraging longer stays reduces per-person transportation impact. Sourcing locally minimizes supply chain emissions. Maintaining landscape biodiversity provides ecological benefits that offset operational impacts. Educational programming creates ripple effects as visitors carry sustainability lessons home. The calculus isn’t perfect, but it’s honest and constantly improving.

Privilege and Access

Heritage properties carry complicated class histories, and Ballinderry Park is no exception. For much of its 700 years, the estate represented aristocratic privilege and, at times, exploitative relationships with surrounding communities. Contemporary operations risk reproducing these dynamics if not carefully considered. When sustainable local food is priced out of reach for local families, when the estate becomes a playground for wealthy tourists while providing only service jobs to residents, the sustainability claimed becomes hollow.

Addressing this requires ongoing vigilance and structural choices. Community programming creates access beyond commercial transaction. Local sourcing creates economic benefit beyond estate employment. Educational initiatives share knowledge rather than hoarding it. The goal is sustainability that includes rather than excludes, that empowers communities rather than displacing them. This work is never finished.

The Scale Question

Perhaps the most significant limitation is the question of scale. Ballinderry Park’s model works beautifully for a 700-year estate with significant land, built heritage, and institutional support. But can it scale to address society-wide sustainability challenges? Can its lessons apply to suburban developments, urban centers, or regions without similar heritage assets?

The answer is both yes and no. The specific model doesn’t scale—most places aren’t historic estates. But the underlying principles absolutely scale: prioritizing local sourcing, building community partnerships, preserving existing structures, integrating human activity with ecosystem health, creating spaces of conviviality rather than mere consumption, resisting disposable culture. These principles can manifest in radically different forms while maintaining philosophical coherence.

Ballinderry Park’s value isn’t as a universal template but as a demonstration site—proof that sustainability aligned with heritage, community, and pleasure is possible. Other contexts require different expressions of the same underlying values, but the existence proof matters. It contradicts the cynical assumption that sustainability requires sacrifice, austerity, or the abandonment of beauty and tradition.

Lessons for Broader Sustainability Movements

What does Ballinderry Park teach us about sustainable living beyond its specific context? Several lessons emerge with broader applicability.

Sustainability is Cultural, Not Just Technical

Most sustainability discourse focuses on technical solutions: renewable energy, electric vehicles, carbon capture, regenerative agriculture techniques. These matter, but Ballinderry Park demonstrates that sustainability is fundamentally a cultural challenge requiring changes in values, relationships, and ways of being. The technical solutions follow naturally from cultural shifts. When people care about place, they protect it. When communities value conviviality over consumption, sustainable practices emerge organically.

This suggests that sustainability movements should focus as much on creating experiences of sustainable abundance—spaces like Ballinderry Park where people can taste, see, and feel what sustainability offers—as on technical advocacy or policy change. People protect what they love, and love requires experience, not just information.

Heritage and Innovation Aren’t Opposites

Modern sustainability rhetoric often positions itself in opposition to tradition, as if sustainable futures require breaking with the past. Ballinderry Park demonstrates that heritage and innovation can be complementary. The estate’s most innovative aspects—its closed-loop food systems, its ecological management practices, its community partnership model—draw deeply on traditional estate management wisdom while adapting it to contemporary contexts.

This suggests sustainability movements should mine traditional ecological knowledge more deeply rather than dismissing pre-industrial practices as primitive. Cultures sustained themselves for millennia before fossil fuels, and their methods contain crucial insights for post-carbon futures. The innovation lies in adapting rather than abandoning this wisdom.

Scale and Intimacy Matter

Ballinderry Park’s model works partially because of its human scale. Visitors can grasp the full system—from deer in woodland to venison on plate—without overwhelming complexity. Staff can develop intimate knowledge of the land. Producers can maintain direct relationships with the estate. This intimacy enables accountability and care impossible in industrial systems.

This suggests that sustainable alternatives require not just better technologies but appropriate scale. Regional food systems, local energy generation, community-based conservation—these work better than centralized industrial alternatives not because they’re quaint but because they operate at scales where human intelligence, relationship, and care can function effectively. The challenge is supporting these appropriately-scaled systems within economies biased toward consolidation.

Sustainability Requires Patience

Perhaps the most important lesson from Ballinderry Park’s 700-year continuity is the necessity of patience. Sustainable systems aren’t built overnight. They emerge from decades of careful stewardship, mistakes corrected, relationships deepened, knowledge accumulated. The mature woodland ecosystems, the agricultural practices adapted to specific soils, the buildings weathered to beautiful patina—all of this took time.

Contemporary culture’s demand for instant results undermines sustainability at a fundamental level. We want quick fixes, immediate returns, rapid transformation. But ecological systems don’t work on quarterly cycles. They work on generational timeframes. Any serious sustainability project must embrace patience, planning beyond the lifetime of those who initiate it, building foundations that descendants will complete.

A Living Blueprint: From Ballinderry to Everywhere

Ballinderry Park isn’t perfect, and it doesn’t claim to be. It’s a work in progress, constantly refining its practices, learning from mistakes, adapting to new challenges. But its significance lies precisely in this honest, ongoing effort to build sustainability grounded in heritage, community, and place.

For visitors, the estate offers a tangible experience of what sustainable living can look like—not as deprivation but as abundance, not as sacrifice but as richness, not as turning backward but as moving forward with wisdom carried from the past. For East Galway communities, it demonstrates economic development aligned with conservation rather than opposed to it. For other heritage properties, it provides a blueprint for preservation through use rather than static conservation. For sustainability movements broadly, it proves that environmental stewardship, cultural preservation, community development, and human pleasure can align rather than conflict.

The future imagined at Ballinderry Park isn’t a return to some idealized past. It’s a future where we carry forward the best of what previous generations learned—about living within ecosystem limits, building community resilience, creating beauty that endures, caring for places across generations—while adapting these lessons to present circumstances and future challenges. It’s a future where estates like Ballinderry Park function not as private preserves but as commons held in trust, as places where people gather to remember what sustainable abundance feels like, as schools where ecological and cultural wisdom passes to new generations.

The Path Forward

Ballinderry Park’s model of heritage-led sustainability offers several concrete pathways for broader adoption:

- Estate Partnership Networks: Creating collaborations between heritage properties to share best practices in sustainable management, local sourcing, and community engagement

- Educational Expansion: Developing formal programs that train the next generation of heritage stewards in both conservation and sustainability

- Regional Food System Development: Scaling the local sourcing model by connecting multiple institutions with regional producers, creating market stability for sustainable agriculture

- Community Land Trusts: Exploring ownership structures that ensure long-term stewardship while providing community input and benefit

- Documentation and Knowledge Sharing: Recording the practical lessons of heritage-led sustainability so other properties can adapt these approaches

Join the Movement Toward Heritage-Led Sustainability

Ballinderry Park’s vision grows stronger with every person who engages. Whether through visiting, volunteering, or simply supporting the model, you can be part of building sustainable futures rooted in place.

Conclusion: The Radical Act of Staying

In a culture defined by mobility, disruption, and constant reinvention, perhaps the most radical act is simply staying. Staying with a place long enough to know it deeply. Staying with a practice long enough to master it. Staying with a community long enough to build trust. Staying with a building long enough to become a worthy heir to those who built it centuries ago. Staying with a vision long enough to see it mature beyond initial imagination.

Ballinderry Park’s 700 years represent sustained staying, and that continuity itself models sustainability more powerfully than any single practice or technology. It demonstrates that humans can, in fact, maintain their home places across generations, that we can be inhabitants rather than exploiters, stewards rather than consumers, ancestors to those who come after rather than those who burn bridges behind them.

The sustainable living practiced at Ballinderry Park isn’t about returning to some pre-modern existence, nor is it about applying cutting-edge green technology. It’s about the hard, patient work of building systems that can persist—food systems that regenerate rather than deplete, communities that strengthen rather than fracture, landscapes that remain beautiful and productive across centuries, heritage that enriches rather than burdens future generations.

This is the blueprint offered by Ballinderry Park: not a technical manual but an invitation to different relationships with place, community, heritage, and time. It’s an invitation to abundance that doesn’t depend on exploitation, to beauty that doesn’t require destruction, to tradition that enables rather than constrains flourishing. It’s an invitation to stay, to root, to care, to build, to preserve, to participate in something larger than ourselves that was here before we arrived and will persist after we’re gone.

That invitation stands open. The estate’s gates welcome those willing to see sustainability not as sacrifice but as a return to deeper forms of wealth—the wealth of community, the wealth of place, the wealth of heritage maintained, the wealth of land cared for, the wealth of food that tells stories, the wealth of spaces that bring people together, the wealth of futures secured for generations not yet born.

Seven hundred years is a long time, long enough to prove that human habitation can heal rather than harm, enhance rather than diminish. The question Ballinderry Park poses to all of us is simple and profound: What are we building that will endure? What are we preserving for those who come after? What are we doing today that our descendants will thank us for seven centuries hence?

These are the questions that matter in an age of ecological crisis and cultural fragmentation. These are the questions Ballinderry Park asks not through lecture but through embodiment, not through guilt but through invitation, not through sacrifice but through demonstration that sustainable living, properly understood, offers not less but more—more beauty, more connection, more meaning, more joy, more future.

The work continues. The land requires care. The buildings need maintenance. The community seeks strengthening. The vision evolves. But the foundation holds firm: a commitment to stewardship across generations, to heritage as living gift rather than dead burden, to community as source of resilience, to land as partner rather than property, to sustainability not as technical achievement but as cultural practice woven through daily life.

This is the radical ordinary of Ballinderry Park—sustainable living not as extraordinary achievement but as the restoration of normal human relationship with place and community. It’s a normal we nearly forgot, a normal industrial modernity almost destroyed, a normal that now appears revolutionary simply because we’ve strayed so far from it. But it’s a normal worth recovering, worth fighting for, worth building toward. And Ballinderry Park proves it’s possible.

Working with community to build a better future isn’t about inventing something unprecedented. It’s about recovering wisdom nearly lost, rebuilding relationships nearly severed, restoring systems nearly destroyed. It’s about remembering what sustainability meant before the word existed: the simple, profound commitment to leave places better than we found them, to care for what’s been entrusted to us, to pass on to future generations not just resources but a living inheritance of beauty, community, and possibility.

About the Author

Rowan Stainsby

Rowan is a marketing professional and founder of Kraft Digital Agency. In 2024, he and his wife Laoise purchased Ballinderry Park, a stunning Georgian house dating back to c.1740 in County Galway. Together, they are passionately restoring this historic property and documenting the journey on their YouTube channel 'Call of the Curlew'. With a vision to create a space where busy people can unwind, Rowan oversees the transformation of Ballinderry Park into a luxury destination for stays, weddings, and events while honoring its remarkable 700-year heritage.